Benin bronzes: blood legacy

The Gliese Bimonthly Volume 07, exploring the Kingdom of Benin and its stolen art

There in a foreign land, behind glass cases, were heirlooms whose significance was lost on the vast majority of the museum-visitors sauntering by.

Victor Ehikhamenor

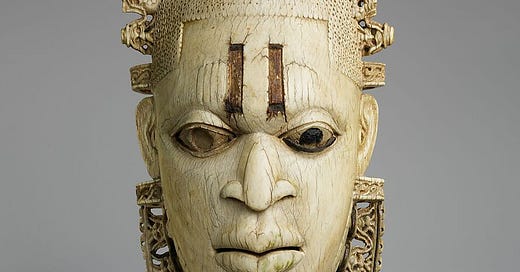

The Benin bronzes are a group of over 5,000 heavily debated sculptures originating in the Kingdom of Benin, which is now located in the Edo State of Nigeria. They consist of sculptures, plaques, figures, and ornaments, originally presented to the Oba (king) in Edo. The bronzes honored the Obas and Queen Mothers and laid at their altars. They were violently stolen by the British in 1897 and are now in a tug-of-war for repatriation.

The Kingdom of Benin

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as Great Benin, was a West African kingdom that existed from 1180 to 1897, when it was destroyed by the British. It shares no historical overlap to the current country of Benin, which was previously called Dahomey. The capital city was called Edo, and is now called Benin City. During the 1400s and 1500s, Benin was a powerful expansionist empire that produced large amounts of artisans. They worked with ivory, bronze, and iron to create several different types of sculpture art. In the late 1400s, Benin began a small amount of trade with Europeans, but the majority of its trade was with their vast internal territory of the entire coastline from the Western Niger Delta, from Lagos to Accra. In the mid-nineteenth century, Britain desired closer trade relations to seek control over Benin, but protectorate measures such as the banning of any exports outside of palm oil and a strong sense of independence prevented the repeated treaties from taking root in the kingdom. British merchants took issue with their failure to comply, and spread baseless propaganda such as consul Richard Burton’s 1862 description of Benin as a “gratuitous barbarity which stinks of death”, with accounts of human sacrifice used as justification for the later Massacre. There is no historical evidence to account that the later Benin Kingdom participated in the mass human sacrifice rituals described by Burton and others. The Gallwey Treaty of 1862 gave Britain greater influence over the Kingdom, leading to the Massacre of 1897, in which areas of Benin City were deliberately destroyed, and palace art was stolen as war booty. Buildings, homes, sacred sites and areas were desecrated by the British.

Who created the Benin bronzes?

In Western museums featuring stolen historical art, the original artists are often neglected or only mentioned in passing. The creators of the bronzes were skilled artisans who were commissioned to create objects of a variety of materials which would be presented to the Oba. They were part of a guild that would specifically create items for the royal court, and were of high ranking in Edo society. Some of these items included “commemorative heads, plaques, royal regalia, animal and human figures, and personal ornaments”1.

Where are the Benin Bronzes now?

Over 900 of the stolen Benin bronzes are in the British Museum. Others are privately traded around the world or are in other museums. Only small commitments have been made by countries that hold Benin artifacts to return them to the place of origin, and only one bronze has been returned by the British Museum.

Arguments and Objections to Repatriation

Proponents of returning the bronzes argue that their removal and subsequent exhibition represent a violent legacy of colonialism. Some argue that the bronzes, among other pieces collected through pillaging and destruction, should remain in colonial museums such as the British Museum. They argue that the methods of obtaining the artifacts are irrelevant if they are used for historical learning, or they argue that museums in the piece’s home country do not have the capacity or resources to sufficiently care for those artifacts.

Nigeria has been working towards repatriating the stolen bronzes since the 1930s before their independence. In 2007, the Benin Dialogue Group was created, a party from both Nigerian and European institutions that aim to bring the artifacts back to Benin City. The group regards repatriation as a powerful symbol of reclamation, both culturally and spiritually.

Another voice of dissent for returning the bronzes to Nigeria is the Restitution Study Group. The RSG filed a lawsuit when the Benin bronzes that were being moved from the Smithsonian Museum in DC to Nigeria, arguing that since the bronzes were used to sell enslaved people in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, descendants of enslaved people are also entitled to the bronzes. The Restitution Study Group executive director, Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, explains that a specific type of bronze bracelet— manillas— were used as currency with Portuguese traders to sell human beings. Manillas were melted down to create some of the Benin bronzes that were pillaged in the 1897 massacre. However, she also argues that she does not want to have to travel to Nigeria, citing US travel warnings.

Many Nigerian-Americans have spoken out against the RSG. Artist Victor Ehikhamenor has said “The exact land from where these things were taken has not shifted,” even if there are historical complications, arguing for repatriation. Nigerian art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu, who is also a professor at Princeton University, disagrees with Farmer-Paellman’s arguments about not wanting to travel to Nigeria, as thousands of Nigerian-Americans travel to Nigeria annually for the Yoruba Osun Osogbo festival.2

Generations of Africans have already lost incalculable history and cultural reference points because of the absence of some of the best artworks created on the continent. We shouldn’t have to ask, over and over, to get back what is ours.

Victor Ehikhamenor

More from GAC

We’re an art collective: outside of our Substack, we publish free zines about non-Eurocentric art history. Our March 2025 issue will be published at the end of the month, and includes four zines. More zines are accessible on our website, gliese.arceus.day.

On March 22, 2025, Michaela Frey’s play will be have a stage reading at Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in downtown Washington, DC. She won third prize in the Mosaic Theater Playwriting Contest. Her play, Meetings on Tilted Ground, is centered around discussions of museum repatriation and Orientalism. The synopsis of the play is as follows: “A foreign scholar, a collector, and a judge meet at a coffee shop to discuss what to do with a retrieved artifact. Two men meet to discuss a treaty on behalf of their states. Time starts and stops between conversations that may not be conversing at all.” All are welcome to attend the stage reading!

"The Benin Bronzes: Rediscovering the Rich Cultural Heritage of the Kingdom of Benin." Roots 101, www.roots-101.org/news/the-benin-bronzes-rediscovering-the-rich-cultural-heritage-of-the-kingdom-of-benin.

"Benin Bronzes: The Struggle to Return Africa’s Stolen Treasures." BBC News, 4 Nov. 2022, www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-63504438

Article written by Michaela Frey