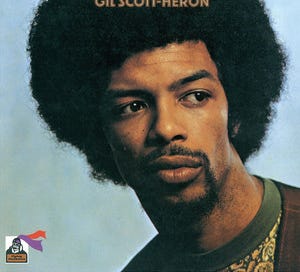

"The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" - Gil Scott-Heron

Our visual interpretation and analysis of the famous 1971 release, in music video form.

When Kendrick Lamar quoted Gil Scott-Heron during his halftime performance at the 2025 Super Bowl, a wave of applause rippled through the crowd, not just for the beat, but for the history. More than 50 years after it was first released, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” still speaks directly to the state of American media, politics, and protest. Scott-Heron’s words remain urgent because the conditions that shaped them haven’t disappeared, but rather, they’ve evolved. This newsletter explores why this 1971 track continues to echo across generations, and what it means when the revolution is reduced to spectacle.

Our Music Video:

“The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” by Gil Scott-Heron was released on April 19, 1971, originally recorded for Scott-Heron’s album Small Talk at 125th and Lennon. The song was written in the era of Black Power in the 1960s; Scott-Heron classified himself as a jazz-poet. A poem sung in spoken word form, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” is considered a form of “proto-rap” and a precursor to the hip-hop music genre pioneered by African-Americans. Delivered over jazz-inspired instrumentals, the song retains elements of traditional African beat, with bongos and conga drums as well as modern flute improvisation. Additionally, the steady beat and rhythm and lack of typical melody as a result of the song’s spoken word format emphasize its message over musicality.

Lyric Analysis

The song begins with the second-person pronoun “you” as Scott-Heron repeats the phrase “you will not be able to” throughout the first stanza, immediately calling the audience to action and setting a precedent for the remainder of the song. The title of the song is first listed in the second stanza, with a double repetition of the phrase “the revolution will not be televised”. In this same stanza, Scott-Heron references and alludes to political figures such as Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew, indirectly criticizing those in power; ultimately, Scott-Heron argues that the political action is not spearheaded by political figures, rather common, everyday individuals.

Scott-Heron continues this form of parallel structure and repetition of the song’s title throughout the following stanzas, alluding to common television advertisements at the time, including weight loss and other appearance-related products. Through mentioning the copious amounts of advertisements on television, Scott-Heron argues that the U.S.’ consumerist and commercialized culture has influenced sedentary lifestyles as corporations have commodified many aspects of American life.

At around the 1:07 mark, in the third stanza, the listing becomes intensified and layered and Scott-Heron increases the pace of his speaking and the instrumentals ramp up, a verbal overload that mimics the barrage of media messages Americans experience. In particular, the jazz-inspired flute line begins to improvise expeditiously over Scott-Heron’s voice, pulling attention to the song’s climax. Scott-Heron switches from anaphora of “you will not be” from the first stanza and the song’s title of the second, to repetition of phrase “there will be no pictures” as he utilizes slang diction in the first line—“pig”, referencing law enforcement—critiquing sensationalized police brutality news outlets portray over television.

Additionally, he explicitly introduces civil rights movements directly, through mentioning Whitney Young, Roy Wilkins, and alluding to Pan-Africanism through the colors red, green, and black of the flag as well as alluding to second-wave feminist liberationists, ultimately criticizing the way media portrays them in a light that diminishes them of their accomplishments in activism.

Furthermore, in the next stanza, Scott-Heron draws back to the entertainment industry, and mentions a myriad of celebrity and media figures by name—all white—as figures emblematic of a whitewashed, sanitized America, asserting that these individuals, as apart of the power-majority and agents of the status quo entertainment industry, will not be part of the revolution, essentially reinforcing that political action will not be driven by familiar figures.

Toward the end of the song, the imagery intensifies once more as Scott-Heron continues directly referencing and alluding to entertainment mediums, including quoting slogans from brands such as Coca Cola, Dove, and Exxon. Through these quotes, Scott-Heron builds relatability with the audience, as many Americans are likely to recognize at least one of the extensive references Scott-Heron introduces, and illustrates how consumer culture numbs the public and distracts from injustices. Calling back to the song’s first lines of “you will not be able to to stay home, brother / plug in, turn on and cop out,” Scott-Heron defends that individuals, specifically Black Americans, cannot utilize entertainment media or news outlets as a means to distract themselves from the systemic abuses occurring in their real lives.

Finally, Scott-Heron ends the song by continuing the parallelism of repeating “the revolution will not be televised,” then switching to “the revolution will be live,” as the song settles back to the original tempo and laid back instrumentals from the start of the song. This final turn ultimately resolves all the build up from the song’s three minutes of abundant references toward all aspects of media—TV shows, celebrities, brands—asserting Scott-Heron’s argument towards the audience that revolution is an active, not passive movement.

Historical Context

Released in 1971, Scott-Heron’s poem connects directly with the Civil Rights Movement and the rise of more radical Black political thought in the late 1960s and early 1970s—Black Power, coined by activist Kwame Ture. Scott-Heron’s critique parallels the shift from nonviolent protest from sit-ins to more self-determined movements like those led by the Black Panther Party. The civil rights movements of the 1960s coincided with changes to a variety of news and communications media, with television coverage of news expanding rapidly to bring awareness and accessibility to these movements. His criticism of corporate influence and the media aligns with how consumerism shaped American culture post-World War II with the boom of commercialization. Suburbanization, TV ownership, and brand loyalty became symbols of American prosperity, but for many Black Americans, these promises were hollow as they remained excluded from the benefits of the GI Bill, housing loans, and educational access in this era of segregation.

Moreover, Scott-Heron’s references to the Vietnam War and politicians such as Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew highlight how media and political institutions ignored or distorted revolutionary action, wherein televised reports often contradicted official government narratives. Although the Watergate scandal had not yet occurred at the time of the song’s release, Scott-Heron would likely make reference to it as a confirmation that American political leaders were fundamentally disconnected from the struggles of the American people as blatant government corruption became visible through coverage of this scandal.

Overall, the song captures the frustration many Americans, especially Black Americans and anti-war activists, felt toward institutions that claimed to represent them but often worked to suppress or co-opt real change, but also the passivity of many individuals and lack of action from them to change the status quo and influence societal progress.

Ultimately, through repetition, cultural references, and critiques of media portrayal of protest, Scott-Heron conveys that political action is not entertainment, and civil rights movements in the 60s and 70s were driven by community organizing and tangible movements, not media glorification or portrayals of it, and the phrase “the revolution will not be televised” has become a cultural reference in it of its own.

References:

https://genius.com/Gil-scott-heron-the-revolution-will-not-be-televised-lyrics

https://www.carnegiehall.org/Explore/Articles/2022/01/11/Timeline-of-African-American-Music

https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/roy-wilkins

🔥🔥