Art and Resistance: the Afrofuturist lens

Gliese Bimonthly Vol. 1, covering afrofuturism in the world of art and music.

“Most people go blind in blackness. I have a fire in my eyes. I have that whole collapsing sun in my head, my visual tectum shorted wide open, jumping, leaping, sparking. It’s as though the light lashed the rods and cones of my retina to constant stimulation, balled up a rainbow and stuffed each socket full. That’s what I’m seeing now. Then you, outlined here, highlighted there, a solarized ghost across hell from me.”

- Samuel R. Delany, Nova (1968)

Afrofuturism: the promise that Black people exist in the future, the present, and the past. It focuses on the “alien nation” of the African diaspora, sun-filled futures, and a distinctive optimism to fill spaces and places where African Americans were omitted with stories of joy and Black life.

Afrofuturism examines the future through a lens that addresses the injustice of four hundred years of oppression. Afrofuturist artists utilize this perspective to create unique and innovative art that reflects the African diaspora experience. This style combines elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, Afrocentricity, and magic realism with non-western beliefs. Afrofuturism’s vast genre and aesthetic, whether through literature, visual arts, music, or grassroots organizing, redefined culture and notions of Blackness for today, and in the future, both an artistic aesthetic and framework for cultural theory.

Afrofuturist artists

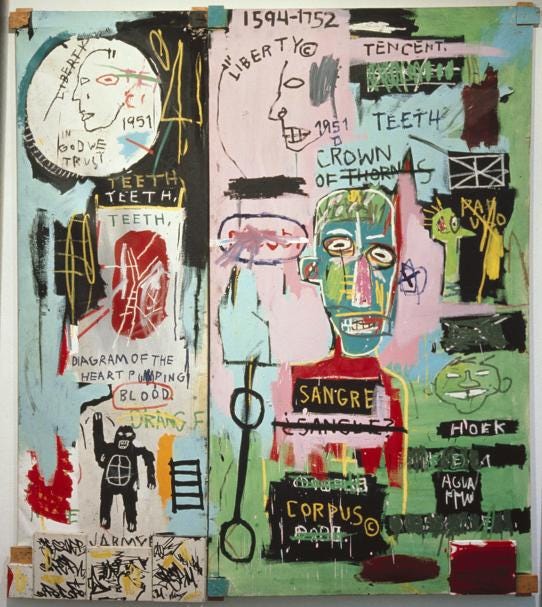

Jean-Michel Basquiat | Paintings

Basquiat’s paintings mix African and Caribbean symbols with cryptic text, urban imagery, and bright colors, reflecting an intense exploration of Black identity in modern society. His work examines colonialism, oppression, and rebellion, making him a key influence in Afrofuturist visual art.

Wangechi Mutu | 3D Art

Mutu’s collages and sculptures often feature Black, hybrid forms that combine human, animal, and alien traits. Her pieces critique colonial history, gender, and race while imagining Black women as powerful, mythical beings who exist beyond current definitions and limitations.

Kerry James Marshall | Paintings

Marshall’s paintings center on Black life and community, often reworking traditional European styles to focus on Black subjects. His use of Black figures in dreamlike, abstracted scenes reclaims art history spaces that often excluded Black perspectives.

Nick Cave | Mixed media

Known for his wearable sculptures called “Soundsuits,” Cave’s work combines dance, performance, and sculpture. The Soundsuits act as armor and symbols of resilience, often made from materials that reflect Black cultural heritage. His pieces challenge social issues, like racial profiling and identity, in visceral, performative ways.

Afrofuturism in music

In “Is This the Future? Black Music and Technology Discourse,” Nabeel Zuberi writes that Black music culture seems an appropriate portal through which to examine the emerging media architecture of remembrance and to investigate perceptions of technological change.

Through the mixing of old with new, or “back to old colonial and African drum patterns in [...] computerized riddims,” Black Afrofuturist music refuses to follow a linear path, as Black history is “characterized by ruptures ... that begin with a brutal dislocation, the slave trade,” so black historical materialism is produced in circumstances of “shock, contraction, painful negation, and explosive forces.”

Sun Ra | Experimental Jazz

Perhaps one of the most well-known Afrofuturist composers, Sun Ra, a pioneer of cosmic jazz, led his musical collective The Arkestra in visual and auditory experiences combining futuristic sounds and Egyptian aesthetics. He claimed he came from Saturn to spread peace:

“The world was going into complete chaos... I would speak [through music], and the world would listen. That’s what they told me,”

- said Sun Ra, on his trip to Saturn.

Sun Ra composed music that utilized new technologies, such as tape delay, to enhance the experiences combining the past and the future. As well as sound, Sun Ra used wordplay to augment his stance on the Black future:

“If you want to call [my music free music], spell it _p-h-r-e_, because _ph_ is a definite article and _re_ is the name of the sun. So I play _phre_ music – music of the sun.”

The Arkestra consisted of musicians who played African and Western musical instruments, from violinist and singer June Tyson to artist Bill Sebastian who manned the Outer Space Visual Communicator. Its evolving lineup of over 30 musicians reflected the collective’s non-static, ever-expanding nature.

Grace Jones | New Wave R&B

A Jamaican-American model, singer and actress, Jones released albums that blended new wave, reggae, and dance. She is known for her androgynous fashion and her modeling work that defied gender boundaries and stereotypes.

Released in 1985, her first single “Slave to the Rhythm/Jones to the Rhythm” is famous for its plastic imagery, strange visuals, and invocations of Black history, gender, and industrialization. The song opens, like many other famous Afrofuturist pieces, with a reference to her African ancestors. She says:

"My grandfather's [...] grandfather came from Nigeria, from the Igbo tribe... I don’t look like my mother and I don’t look like my father. I look exactly like my grandfather. I act like him."

The song’s visuals juxtapose references to Igbo heritage with modern, industrial aesthetics. This tension between ancestral pride and futuristic imagery captures the heart of Afrofuturism. As her face appears on screen, it is understood that Jones is unafraid to speak on her Igbo ancestry.

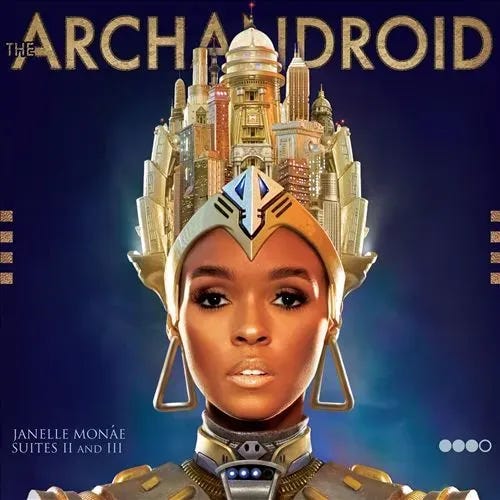

Janelle Monáe | R&B

A singer-songwriter from Kansas City, Janelle Monáe Neo-Afrofuturist music builds on the imaginative legacies of 1970s countercultures like P-Funk. She does so in a way that challenges the traditional ontological structure of such secondary worlds.

Traditional Afrofuturist worlds are often regarded through three themes: Afrocentrism, messianism, and masculinity. It is very solidified, self-aware, and knowing. Monae's work, in contrast, is, according to Zuberi, “elliptical and endlessly ambiguous,” aiming for post-genre as well as post-gender, floating in a hauntological space of unknowing. This in-the-clouds style is a separate strategy of the cause to reconcile the ruptures of Black history, as Zuberi previously put it.

However, the ambiguity does not take away from the real-world impact of Monae's work: The WondaLand Arts Society collaborate as a collective on Monae's work, creating a space for Afrodreamers that defy the previously set boundaries of the movement.

“There's a world inside

Where dreamers meet each other

Once you go it's hard to come back

Let me paint your canvas as you dance.”

- Janelle Monáe, “Wondaland.” The ArchAndroid (2010)

To conclude

Understanding the history of people and myth across the African diaspora illustrates to the community that they do have a place and sci-fi and fantasy spaces. For example: Black representation in science fiction media such as Star Trek inspired generations of children and future astronauts. There is a long history of inspiring artists, writers, musicians, and visionaries to draw inspiration as they engage in their own creative practice.

Afrofuturism is a reminder that the future doesn't have to be a chrome, whitewashed, homogeneous wasteland of dystopia; you can shape what the future of your community looks like by intentionally bringing your heritage into the future and paving a flourishing, culturally, rich path ahead for the rest of us.

Recognition and appreciation of Afrofuturism is a reminder that just like the present, not everyone experiences time in the same way. The future can be one where we celebrate and support each other by recognizing the past and addressing oppressive systems in the present and shaping collectively a future that is diverse, creative and just.

References:

Adade, Arianna. “Afrofuturism 101.” The Phillips Collection, 5 June 2024, www.phillipscollection.org/blog/2024-06-05-afrofuturism-101.

“Basquiat.” Brooklyn Museum, 5 June 2005, www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/basquiat.

Jones, Grace. “Slave to the Rhythm.” Slave to the Rhythm, Island Records, 1985.

Monáe, Janelle. “Wondaland.” The ArchAndroid, Wondaland Arts Society, 2010.

Space Is the Place. Dir. John Coney. Perf. Sun Ra, The Arkestra. 1974

Tomkins, Calvin. “The Epic Style of Kerry James Marshall.” The New Yorker, 2 Aug. 2021, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/08/09/the-epic-style-of-kerry-james-marshall.

“Wangechi Mutu.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/artists/28097.

Washington, Angela. “Afrofuturism in the Stacks.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 15 June 2022, www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/library-afrofuturism.

Zuberi, Nabeel. "Is This the Future? Black Music and Technology Discourse." Science Fiction Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2007, pp. 283-300. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4241526.

Further reading:

Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, Ytasha Womack (2014).

More from GAC

We’re an art collective: outside of our Substack, we publish free zines about non-Eurocentric art history. For our November 2024 issue, we just published three, covering a wide range of topics. Here is a description of each:

The 70’s Biweekly: Youth leftism in Hong Kong — The 70’s Biweekly, a youth magazine that combined Hong Kong’s local arts and culture scene with left internationalism. A prominent example of how grassroots leftism in HK existed and how it persists.

Art in the Three Kingdoms of Korea — We explore art of one of Korea’s ancient periods, the Three Kingdoms of Korea. It offers insight on religious and cultural influences on each kingdom’s art.

Keith Haring — This zine gives insights about Keith Haring, a well-known visual artist, and the influences and cultural contexts surrounding his artwork. Haring’s work includes iconography that reflected his activism.

Click here to access printables of each, on our website!

Written by Amenah Rashid